ROUSES.COM

ROUSES.COM

15

Béchamel Sauce

Makes about 5 cups

WHAT YOU WILL NEED

8

tablespoons unsalted butter

1

shallot, chopped

1

carrot, chopped

½

cup flour

5

cups milk

1

teaspoon ground nutmeg

Rouses salt and pepper

HOW TO PREP

In a large saucepan, melt butter over medium heat.

Add shallots and carrots and cook for 5 minutes.

Whisk in flour and cook 2 minutes. Whisk in milk

and bring mixture to a boil. Reduce to low heat and

simmer, whisking occasionally, until sauce is thick,

about 20 minutes. Add nutmeg and season with

Rouses salt and pepper.

Turn this into

Mornay Sauce

by adding

Gruyere cheese or

Soubise Sauce

by adding

sautéed onions and tomato puree.

Velouté Sauce

Makes about 2 cups

WHAT YOU WILL NEED

3

tablespoons butter

3

tablespoons flour

2

cups chicken or veal stock

Rouses salt

Freshly ground white pepper

HOW TO PREP

In a medium saucepan melt butter over medium

heat. Stir in flour to create a roux, and cook for

2 minutes. Whisk in stock, ½ cup at a time, until

completely combined and sauce is smooth. Season

with salt and pepper. Bring sauce to a boil, reduce

heat to low, and cook for an additional 15 minutes.

Normandy Sauce

adds mushrooms and a

mixture of heavy cream and egg yolks.

Bercy

Sauce

is great too, with white wine, shallots,

parsley and lemon juice.

FRENCH

The Mother Sauces

by

Chef Chaya – Rouses Bakery Director

O

ne of the first things you learn in

culinary school is that French food is

all about the sauce. And French sauces are

all about that base.

In the 19th century, the chef Marie Antoine-

Carême, the founder of the haute cuisine,

catalogued the list of French sauces into four

foundational or mother sauces. Béchamel is a

white sauce made with butter, flour and milk;

it’s the secret to great macaroni and cheese

and creamed spinach. Velouté is a light sauce

similar to a Béchamel, but made with fish or

chicken stock. Tomat is made with chopped

or puréed tomatoes, that can be smooth

or chunky, depending on your taste. And

Espagnole is a classic brown sauce made

with a darker roux and tomato purée.

In 1903 Auguste Escoffier, another great

French chef, added a fifth foundational

sauce when he published

Le Guide Culinaire.

Escoffier’s textbook and cookbook was

my bible when I studied at the Culinary

Institute of America. His fifth sauce would

strike fear into the hearts of young culinary

students like me. The dreaded Hollandaise,

an emulation of egg yolks, lemon juice

and butter, had to be whipped just right,

or it breaks or separates. I love it on eggs

Benedict, but to this day I get a little

anxious when I think about my first attempt

at making it.

THE FRENCH QUARTER

When I was 18 I did my extern from the

CIA at Arnaud’s on Bienville Street in

the French Quarter, where I was often

assigned to help the saucier make huge pots

of mother sauces. We would make roux

using 50 pound sacks of flour, Béchamel

in steam-jacketed kettles as tall as me, and

Hollandaise in a stand-alone mixer. My

favorite was Espagnole. It would simmer

for 24 hours, so we could extract every bit of

deliciousness from its ingredients.

I will never forget standing over the kettle

with a paddle that stretched all the way to

the floor, the steam billowing up around me,

quoting a line from

Apocalypse Now

, “I was

a great Saucier in New Orleans.” I felt like I

was a part of history.

Arnaud Cazenave, a French wine salesman,

openedArnaud’s on Bienville Street in 1918,

but there are French Creole restaurants in

the French Quarter that date back even

further. Guillaume and Marie Abadie

Tujague, originally of Bordeaux, France,

opened Tujague’s in 1856. Jean Galatoire,

a native of Parides, France, opened his

Bourbon Street restaurant in 1905. The

oldest French restaurant in New Orleans,

Antoine’s, served its first meal 175 years

ago. Antoine’s menu was originally written

entirely in French. Today’s menu is half in

English, half in French, but the sauces are

still all French.

The old line Creole-French restaurants are

famed for the French sauces. At Antoine’s

you can order steak with Marchand du

Vin, a classic red wine sauce; Béarnaise, a

variation on Hollandaise that’s seasoned

with tarragon and white wine; or Aliciatore,

a Béarnaise sauce flavored with sweet

pineapple and lamb or beef that is named

after the restaurant’s founder. Espagnole is

the base for Antoine’s Colbert sauce, which

is the finishing touch to the restaurant’s

famed fried oysters foche.

Mayonnaise, which falls under the category

of Hollandaise, is the base for both maison

sauce (crabmeat maison is a must at

Galatorie’s) and red and white versions of

remoulade. You can’t go wrong ordering

shrimp remoulade at Antoine’s, Galatoire’s,

Tujague’s or Arnaud’s.

THE RECIPES

Once you learn a handful of bases, you can

customize them into hundreds of different

sauces. I scaled these recipes down for home

use. You can turn them into classic sauces,

or innovate by adding your own flair. Either

way you will be creating, and eating, history.

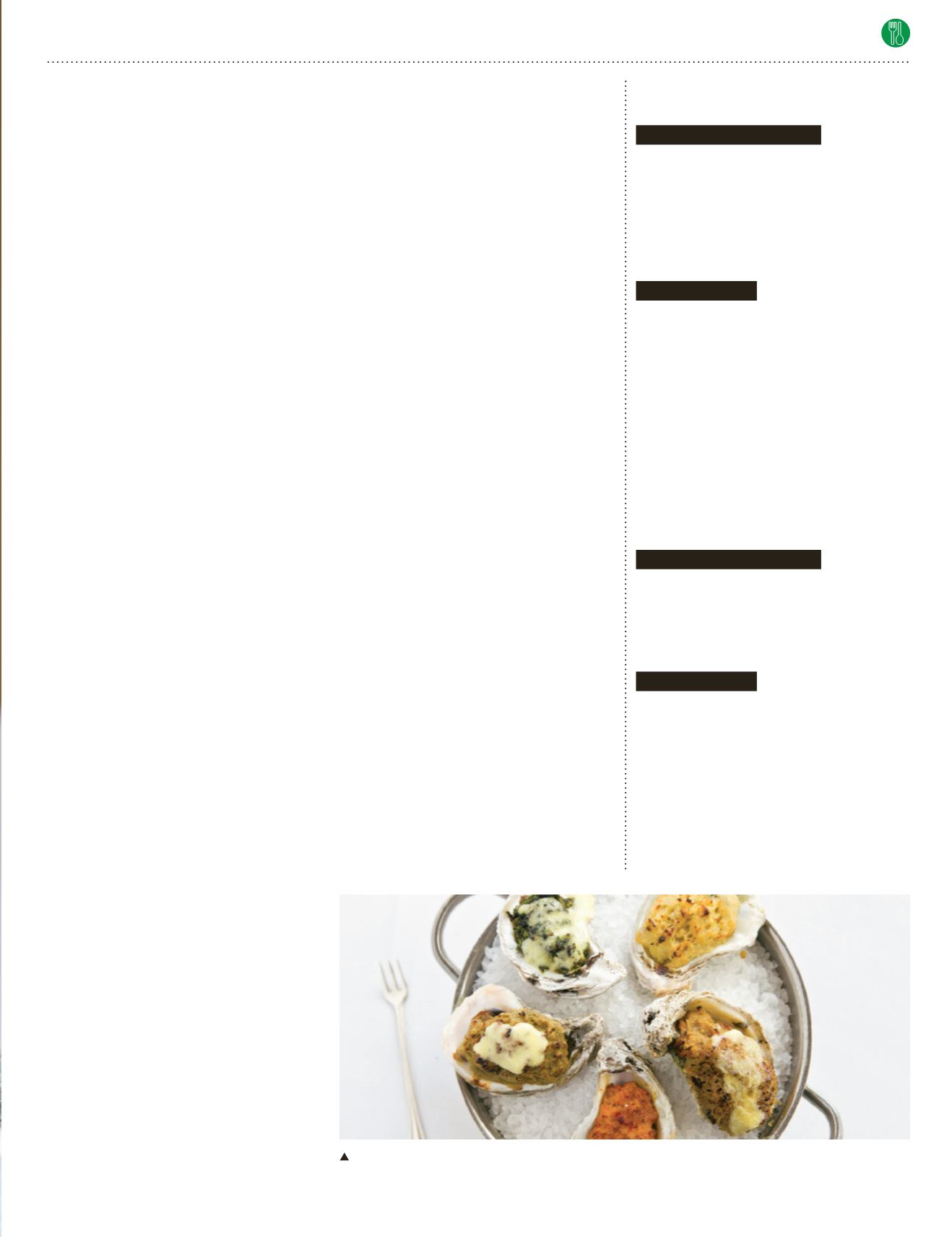

photo courtesy

Arnaud’s Restaurant

by

Sara Essex Bradley