ROUSES.COM

ROUSES.COM

17

F

rench bread in New Orleans is

the story of the desire for the

preservation of tradition when that

preservation is almost impossible. Wheat

did not exist in the New World. So settlers

in Louisiana relied on flour imported from

France and then Spain for their basic bread.

But the bread often arrived riddled with

mold and insects. Although it might have

been easier to bake and eat cornbread, it was

not considered a satisfactory substitute for

wheat bread.

Households might be able to avoid tainted

flour in their bread, if they baked at home.

But home baking was difficult in the area.

As scholar Michael Mizell-Nelson notes,

“Humid conditions made it difficult for

bakers to produce hard crusts and capture

yeast from the air.Few households produced

their own bread, because producing this

elemental part of life generated too much

heat and required too much physical

stamina and skill for most New Orleanians.

Brick ovens fueled by wood fire produced

a hellacious job of cleaning out the embers

every Saturday.”

After the Louisiana Purchase it became easier

to obtain wheat flour from the Midwest. It

arrived in New Orleans and was shipped by

boat and later rail to other parts of the state. It

was very expensive. Wheat flour was 3 times

more expensive in New Orleans as compared

with St. Louis and 6 times as expensive west

of the Atchafalaya Basin.

By the mid 1800s, German and Austrian

bread baking techniques, which included

adding milk to the dough to create a much

lighter airy texture, were becoming popular

across Europe. German bakers in Louisiana

brought this preference for a light texture in

contrast to the denser crumb of traditional

French loaves. Bakers also began to add

sugar and shortening to act as preservatives,

another departure from traditional

methods. But these techniques were well

suited to the humid climate. In addition to

lasting longer, this preference for a lighter

loaf required less flour than the traditional

model, resulting in a cheaper loaf.The shift

in shape from a cap style loaf to a baguette

was influenced by Parisian tastes, when

their fondness for more crust was satisfied

by the elongation of the cap or gigot shape.

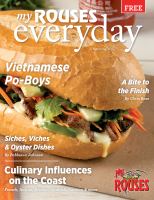

Finally, in the early 20th century, the

growing popularity of “loaves” or “po-

boys” created the French bread known in

New Orleans today. Sandy Whann, of

Leidenheimer Baking Company, believes

that “New Orleans French bread evolved

based on the variety of ingredients used

to make poor boys. The delicate balance

of a thin, crisp crust with enough firmness

to stand up to brown and red gravy and a

lightness that would not compete with

Gulf seafood … a loaf that diners could

readily bite into without cutting the roof

of their mouth, as might happen with

traditional French bread; however, the loaf

had to be strong enough to hold up to gravy,

mayonnaise, and other ‘dressings’.”

Did You KNOWLA?

By the mid-1800s, German and Austrian

bakers dominated the baking trade in

New Orleans; they altered the traditional

French bread into a New Orleans

variant characterized by a much lighter

loaf with a crisp crust. The first “poor

boy” loaves were baked by African

Amercians toiling in a bakery run by an

Italian immigrant who supplied Cajun

restaurateurs in the French Market. This

cycle continues. The recent advent of

Vietnamese cuisine in the city has caused

most Louisiana residents to rebrand

what most Americans know as the “banh

mi” sandwich as a Vietnamese po-boy.”

—

www.knowla.orgThe Encyclopedia of

Louisiana History

French

Bread

by

Liz Williams, Founder &Director, Southern Food & Beverage Museum

FRENCH