46

MY

ROUSES

EVERYDAY

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2014

the

Holiday

issue

It sounds more like a ‘50s dance craze than

a family meal. Or like some character out

of a Dickens novel, the good-hearted but

sketchy town drunk, he of pronounced limp

and dandy cane.

Never mind that the primary characteristic

of Hoppin’ John is also the name of a wildly

popular band from the turn of the century.

(This century, that is; not Dickens’.)

That “characteristic” — ingredient is the

more accurate word here — is black-eyed

peas. You might call them field peas.

(This is as good a time as any for a disclaimer:

This is Southern cuisine we’re talking about

here and there are no absolutes — I will not

be receiving correspondence that takes issue

with any information presented herein as

factual. There is very little that is “factual”

about Southern culture anyway; it’s all

mythology and lore. That’s what makes us,

as a region, so ... interesting.)

But I digress. The dish called Hoppin’

John generally includes rice and some good

Southern stuff like salt, onions and fatback

with those black-eyed peas (which are often

pickled for good measure).

For the winter holidays, the Hoppin’ John

takes on properties loftier than simple

nourishment of the body. This time of year,

the dish will generally include greens of

some kind, including cabbage, a food source

of considerable prominence in Irish culture.

(Unless you have had a wayward cabbage

shatter your car window or knock you

senseless to the ground during a St. Patrick’s

Day parade in New Orleans — each of

which I have personally witnessed — there is

no reason to doubt its auspicious properties.)

On New Years Day in particular, supper

tables across the South are graced by some

form of Hoppin’ John dish or at least black

eyed peas and cabbage, not only to fortify

the bones on a cold winter’s day, but to

invite good luck and great fortune in the

coming year for those who partake.

As with any indigenous superstition,

there are dozens of interpretations and

explanations for each element of the dish,

but the generally held notion is that the

peas are symbolic of pennies, or coins in

general — and it’s true that sometimes a

heaping of these delectable legumes can

sometimes, almost, sort of resemble a pile

of gold nuggets.

Sort of.

Many Hoppin’ John recipes, in fact, call for

a real coin to be added to the pot during the

meal’s preparation. The person who receives

this token in their portion is said to receive

extra luck — the first evidence of which is

that the unsuspecting recipient of a coin

hidden in their stew managed to escape

choking to death.

(Any similarities to the tradition of

inserting little plastic babies into king

cakes during Mardi Gras season in New

Orleans are not coincidental and are the

sole provenance of the sublime nature of

Southern superstitions.)

The greens that flesh out a dish of Hoppin’

John — be they cabbage, collards, mustard,

turnip, chard, kale or some other (are there any

other?) — are meant to symbolize, well, green

— the color of paper currency. In America.

(I have no idea what the French add to their

field peas on New Year’s Day for good luck.

I mean, seriously?)

As if all of this is not enough to keep in

mind, one who participates in a Hoppin’

John repast is also supposed to remember

— upon finishing their meal — to leave

three peas remaining on the plate to ensure

Hoppin’ John

by

Chris Rose +

photos by

Romney Caruso

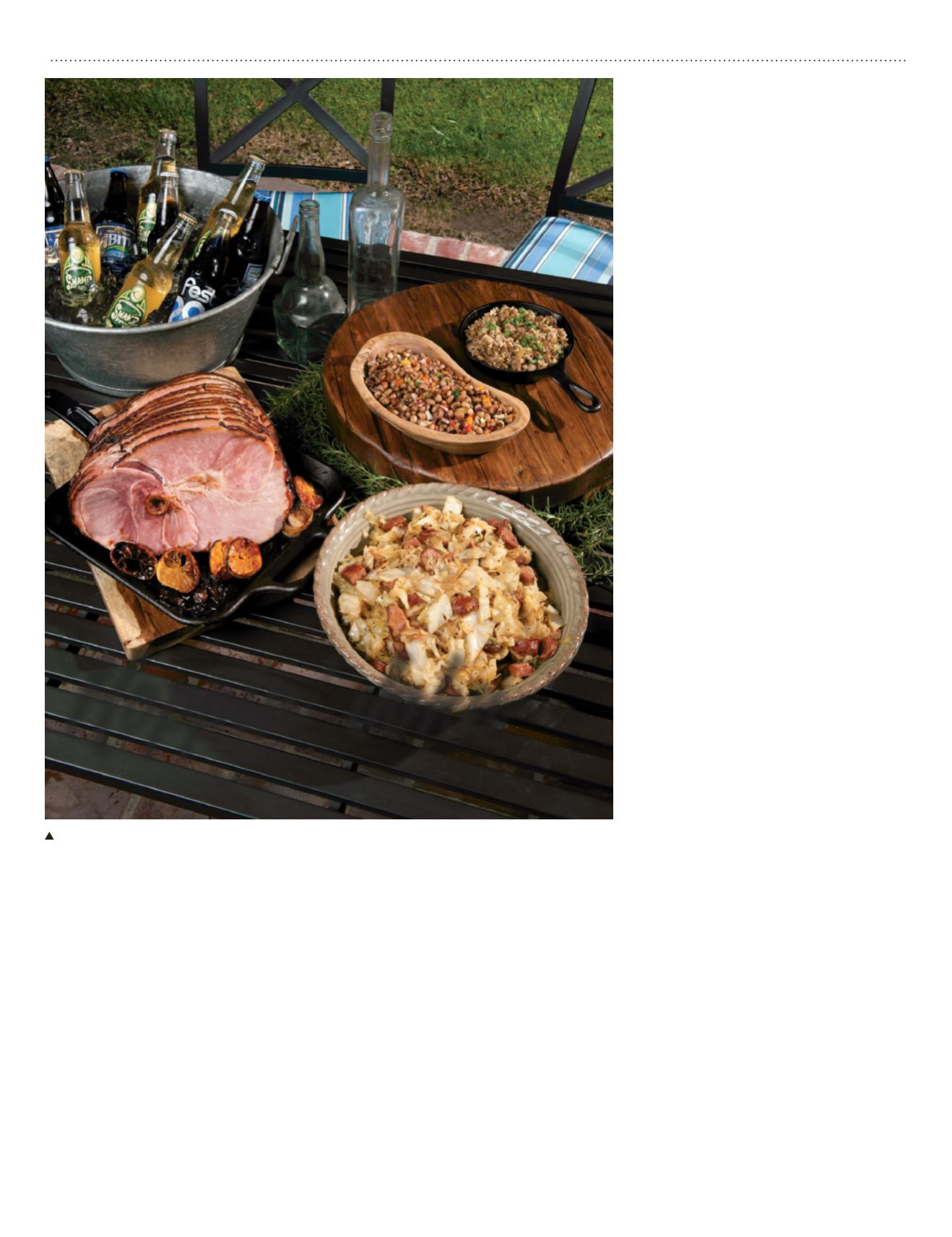

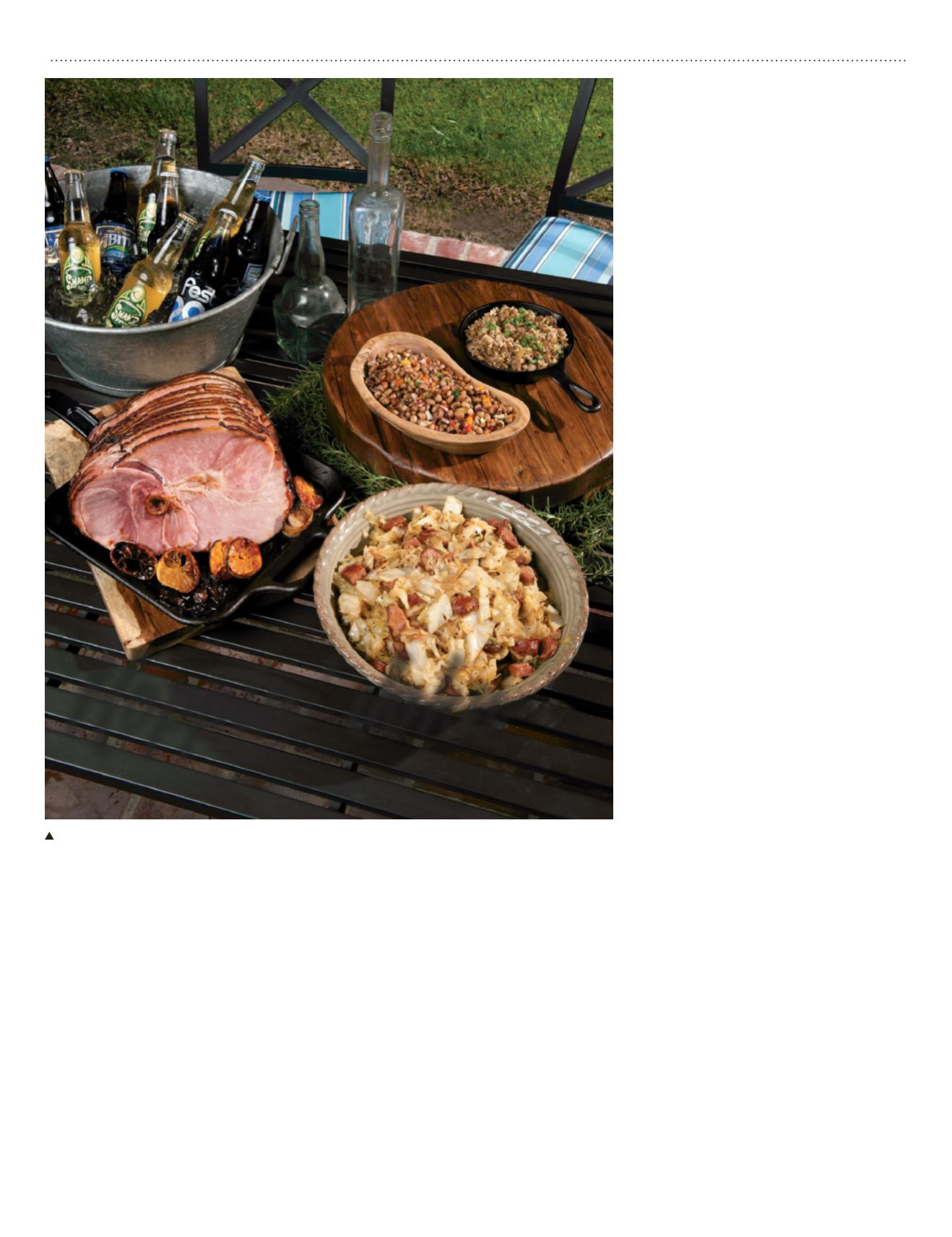

Hwy. 1 New Year’s Day: Spiral sliced ham, black-eyed pea salad, smothered cabbage and ham hocks at Tim Acosta’s house.