26

MY

ROUSES

EVERYDAY

MAY | JUNE 2015

the

Culinary Influences

issue

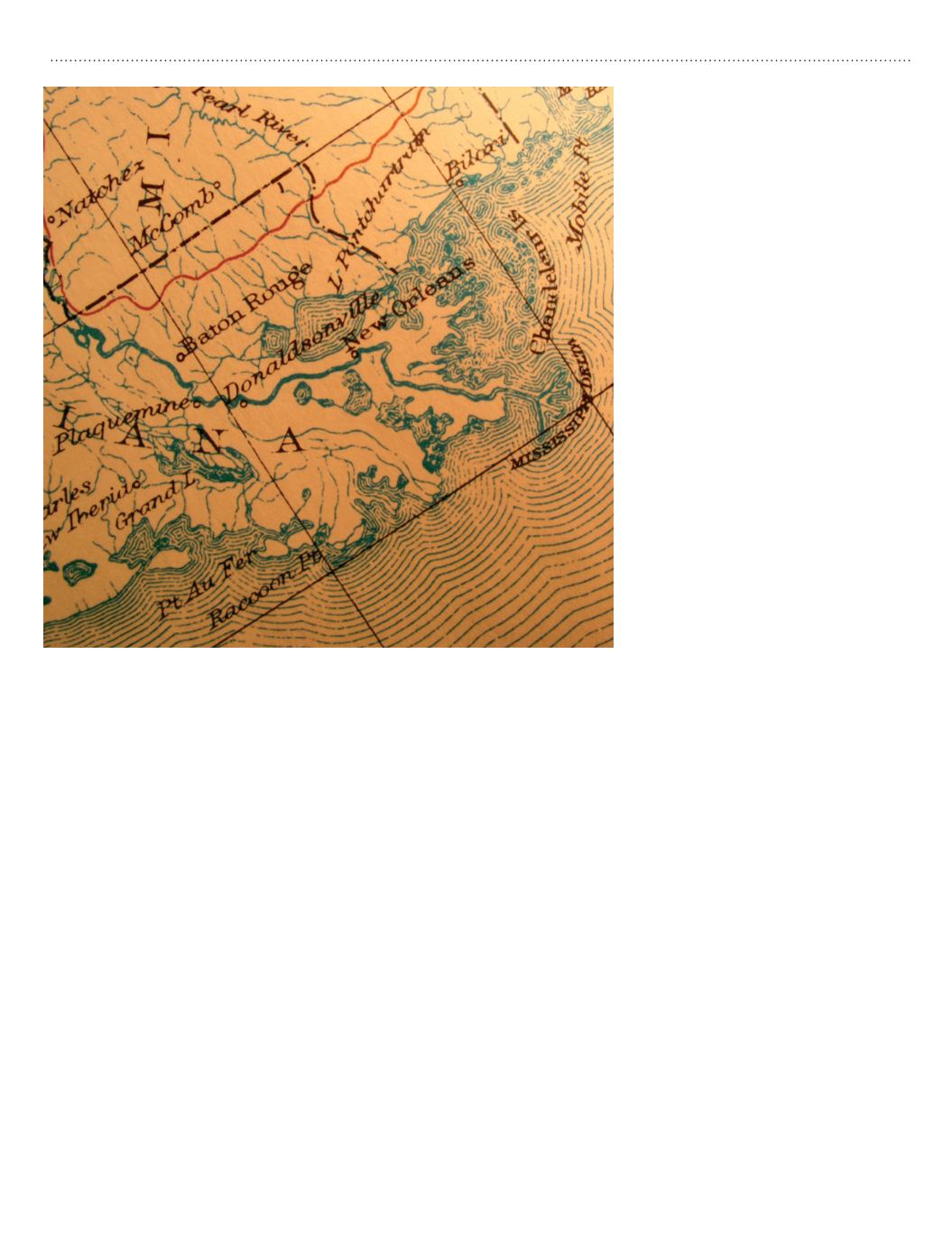

T

he Cajun and Creole cultures are quite distinct, and so are

their cuisines.The Creoles were the offspring born in New

Orleans of the European aristocrats, wooed by the Spanish

to establish New Orleans in the early 1690s. Second-born sons,

who could not own land or titles in their native countries, were

offered the opportunity to live and prosper in their family traditions

here in the NewWorld. It is believed the word Creole can be traced

to one of two origins. First, the old Spanish word “Criallo”meaning

a mixture of cultures or color such as in the word Crayola. Secondly,

from the Latin word “Creare” meaning to create as in creating a

new race. Although the first Creoles were documented in Mobile,

Alabama, in 1702, Natchitoches and New Orleans followed in

1714 and 1718 respectively.Today, the term Creole in New Orleans

represents the native born children of the intermarriage of the

early cultures settling the city. These include the Native American,

French, Spanish, English, African, German and Italian and further

defines the cuisine that came from this intermarriage.

The influences of classical and regional French, Spanish, German

and Italian cooking are readily apparent in Creole cuisine. The

terminologies, precepts, sauces and major dishes were carried

over, some with more evolution than others, and provided a solid

foundation for Creole cooking.

Bouillabaisse is a soup that came from the Provence region of

France in and around Marseilles.This dish is integral to the history

of Creole food because of the part it played in the creation of gumbo.

The Spanish, who actually played host to

this new adventure, gave Creole food its

spice, many great cooks and paella, which

was the forefather of Louisiana’s jambalaya.

Paella is the internationally famous Spanish

rice dish made with vegetables, meats and

sausages. On the coastline, seafoods were

often substituted for meats. Jambalaya has

variations as well, according to the local

ingredients available at different times of

the year.

The Germans who arrived in Louisiana

in 1725 were knowledgeable in all forms

of charcuterie and helped establish the

boucherie and fine sausage making in South

Louisiana. They brought with them not

only pigs but chicken and cattle as well. A

good steady supply of milk and butter was

seldom available in south Louisiana prior to

the arrival of the Germans.

The Italians were famous for their culinary

talents. They were summoned to France by

Catherine deMedici to teach their pastry and

ice cream making skills to other Europeans.

Many Creole dishes reflect the Italian

influence and their love of good cooking.

From the West Indies and the smoke

pots of Haiti came exotic vegetables and

cooking methods. Braising, a slow-cooking

technique, contributed to the development

of our gumbos. Mirlitons, sauce piquantes

and the use of tomato rounded out the emerging Creole cuisine.

Native Indians, the Choctaws, Chetimaches and Houmas,

befriended the new settlers and introduced them to local produce,

wildlife and cooking methods. New ingredients, such as corn,

ground sassafras leaves or filé powder and bay leaves from the laurel

tree all contributed to the culinary melting pot.

I would be remiss if I failed to mention the tremendous influence

of “the black hand in the pot” in Creole cooking. The Africans

brought with them the “kin gumbo” or okra plant from their native

soil which not only gave name to our premier soup but introduced a

new vegetable to South Louisiana. Even more importantly, African

Americans have maintained a significant role in development of

Creole cuisine in the home as well as the professional kitchen.

Creole cuisine is indebted to many unique people and diverse

cultures who were willing to contribute and share their cooking

styles, ingredients and talent.

Obviously, Creole cuisine represents the history of sharing in South

Louisiana. Early on in the history of New Orleans, the Creole

wives became frustrated, not being able to duplicate their old world

dishes with new world products. Governor Bienville helped to solve

this problem by commissioning his housekeeper,Madame Langlois,

to introduce them to local vegetables, meats and seafoods in what

became the first cooking school in America.This school aided them

Cajun

&

Creole

by

Chef John Folse,

The Encyclopedia of Cajun & Creole Cuisine